At Grandma’s House is now available on Amazon.

Come with me back to World War II America, an important time and interesting place. The United States, just emerging from a lengthy Depression, reluctantly entered into a military conflict in Asia and Europe. The people and cities of much of the world suffered widespread death and devastation, a calamity not seen in America. Most of the American men who fought on the warfront have passed away, and not too many of my own generation, who lived through the war years on the homefront, are still around.

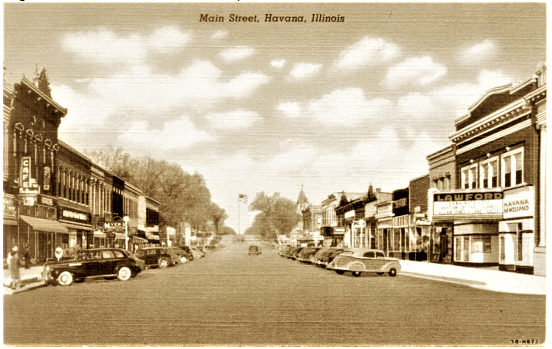

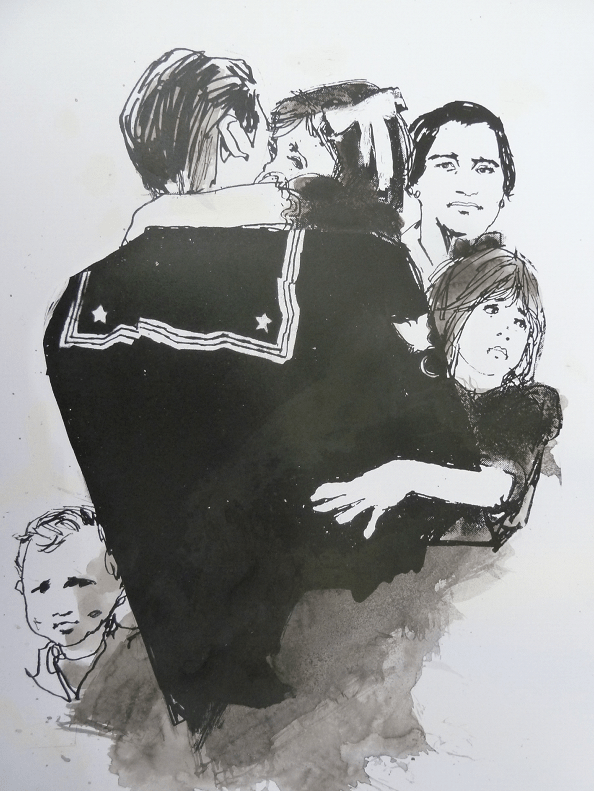

In the early 1940s I grew up in the small town of Havana in central Illinois, and have vivid memories of wartime America, tales I have told to my children and friends. In late 1942 our father enlisted in the navy, depending on his wife to run the family business and raise their three children. My two older sisters and I moved with Mom to her parents’ home—Grandma’s house—where we resided “for the duration.”

Reminiscences of these momentous times are recalled here, supplemented by articles from the 1942-1945 local newspaper. I wrote At Grandma’s House to share and preserve the story of what life was like for the civilian population on the homefront.

Havana’s location close to the geographical center of the United States, and its position as a county seat, make it a typical small town setting of the Midwest, sharing values and attitudes with the rest of the country. Wartime Havana provides a window into the contemporary national scene and the fears and hopes of people who did their best to keep the home fires burning while supporting “our boys” over there.

The words of Charles Dickens, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” fit well into the American drama on the homefront. Although the dark cloud of warfare, and the fate of loved ones fighting battles, hovered over us constantly, nevertheless, all people, especially children, had fun. Much of this story describes the diversions all Americans enjoyed while waiting out the war. In between the best of times and the worst of times was the everyday routine that kept us busy and sane.

The following excerpts from At Grandma’s House give glimpses of the story.

THE BEST OF TIMES ON THE HOMEFRONT

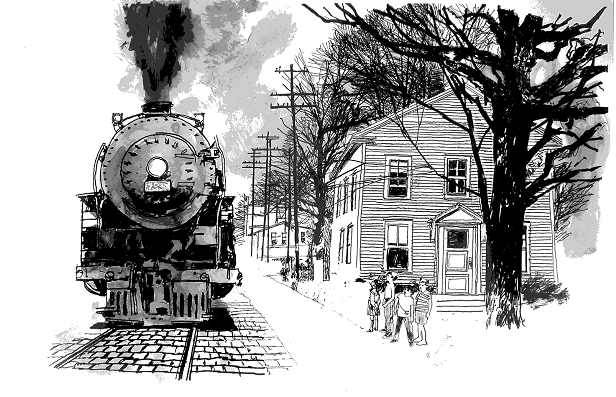

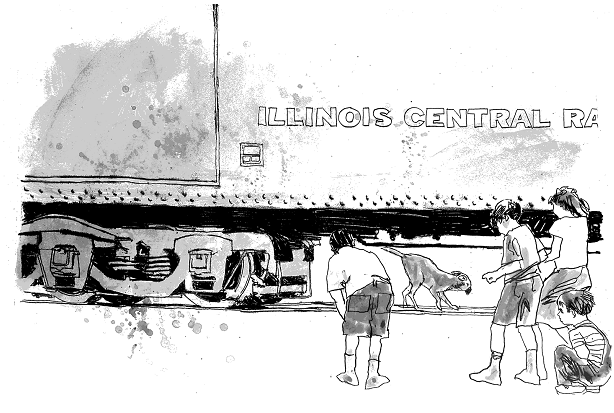

Grandma’s house, on a large corner lot next to “Railroad Street” (now Schrader Street), was situated just a hundred feet from the Illinois Central Railroad tracks to the west. For us children, the powerful locomotives and noisy passenger and freight trains provided an endless source of fascination. The following excerpt, from Chapter 11, shows how the railroad tracks and passing trains provided some frightening and exciting episodes.

[Excerpt from Chapter 11.]

We loved the thrill of being part of the speeding train—the locomotive belching acrid coal smoke that stung our noses, steam from its boiler wafting a light mist over us. The rumbling of the iron wheels on the tracks made the ground vibrate and tickle our bare feet. The swirling air brushed against our faces. To gain the greatest sensory impact from this iron monster, we stood at the very edge of the yard, next to or even perched on the concrete curb. When Grandma saw us fudging on the boundaries, she’d yell “Stay in the yard!”

One day we learned that dogs did not always understand human regulations. Our friend Walter Ray visited us with his dog Popeye, a friendly and playful little mutt, mostly white, but with some black markings, including a black ring around one eye. How he got his name I never heard, but his animated spirit made us think of the cartoon character Popeye.

Walter had ridden to our house on his bicycle, and Popeye tagged along. That summer day, a lot of kids were playing at our house when the train came by. We all stood where we should be, in the yard, but for some reason Popeye ran across the street and darted underneath a passenger train with a half dozen khaki green cars, rushing by at a fast clip. When Popeye loped out towards the train, some of us started to chase after him, while Grandma, watching from the back porch, yelled, “Get back in the yard.”

It horrified us to see the dog slip right under the passing train cars. Popeye became a blur of black and white, spinning around, turning this way and that, hidden from view by the wheels at the end of a car, then briefly visible, and then hidden again. We thought the only thing the dog could do was stay put, so we yelled “Stay there! Stay there!”

Unfortunately, our shouts had the opposite effect. Popeye seemed to hear us, and made a dash from under the train out onto the street and into the yard, without getting so much as a scratch.

Although all of this lasted only a matter of seconds, it scared us enough for a lifetime. Popeye became his playful old self within a few minutes. Grandma found this a good source of moral example to “stay in the yard.”

As clever children we managed to put the train tracks to use for our own amusement, in a fashion never intended by railroad engineers.

[Excerpt from Chapter 11.]

In the long lulls between trains, occasionally we did venture onto the tracks. We never tired of putting pennies on the rails to let the train flatten the coins into roundish and ovalish patterns. Placed just so, the train wheels pancaked the penny into twice its original size. Grandma didn’t really like us to be on the railroad tracks, but if we did it long before the train arrived, she considered it safe, and not a cause for scolding. We knew we had to mind Grandma and her rules, but we had other worries.

In our serious moments, we agreed, “It’s against the law to destroy the government’s money, and if you get caught, they can throw you in jail.”

Whenever someone put a penny on the track, one of us would tease, “Here comes the police!”

The exact placement of the penny required a little knowledge of train technology that we soon mastered. Train wheels have a flange on the inside, which is what keeps the train on the rails. When we positioned the penny (or other coin, if someone felt extravagant) just on the inside edge of the rail, it would be flattened out by the bottom of the wheel and then formed into an “L” shape by the flange. If you put the penny too far to the outside or inside of the rail, the first wheel to hit it knocked it off the track before it was flattened. It took a little practice to put the coin in the right location to produce a mini copper pancake.

THE WORST OF TIMES ON THE HOMEFRONT

The war and the fate of loved ones dominated every aspect of our lives. The local newspaper filled with articles on the draft, enlistments, and the inevitable announcement of wounded and killed. Every American family had a member, or a neighbor, serving in the armed forces. We worried constantly about our loved ones in uniform. The following excerpts reveal episodes of the worst of times.

[Excerpt from Chapter 24.]

The January 30, 1942 issue of the Democrat announced, “LONNIE DUKES KILLED IN ACTION WITH U. S. NAVY. . . SO FAR AS IS KNOWN THE FIRST Mason county boy to give his life in the defense of his country in the present conflict . . . killed on December 7, while on duty with the U. S. Navy.”

These initial casualties of Havana and Mason County, unfortunately, were followed by notices of deaths or wounded military in almost every subsequent issue of the local paper for the rest of the war. Hardened combat soldiers have written that on the battlefield, whether it was the Civil War or later wars, when the ground is covered with dead bodies, one becomes numbed to the victims of the grim reaper, and just walks ahead on the bodies, friend or foe. As I read through the 1942-1945 years of the Mason County Democrat, it became obvious that I could not mention every fallen soldier, marine, sailor or WAAC.

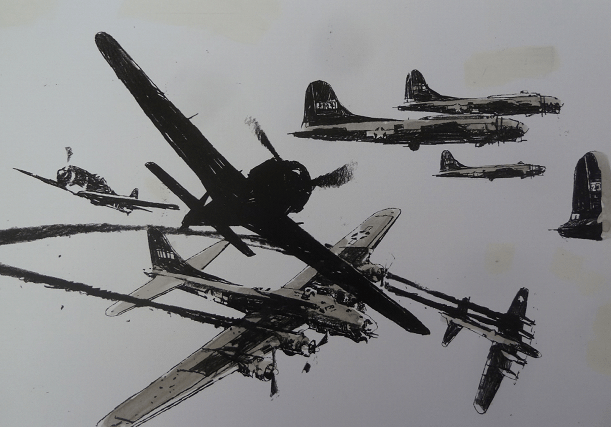

After reading of the deaths of so many local servicemen, I, too, became numb. Then I happened upon the enlistment news of Fred’s son. Fred who had worked at Earhart Food Locker. The picture for Fred’s son showed a handsome young officer in the Air Force. While reading through later Democrat issues, I expected, but dreaded, finding the article a year later recording his death. He had piloted a bomber over Germany, did not return, was presumed lost, then declared dead.

For every parent, sibling, spouse, son or daughter, no number of other deaths can numb you to the pain of the loss of your loved one. When someone you know, your friend, or family member is killed, it is not a statistic. It is a heartbreaker.

[Excerpt from Chapter 19.]

In the early 1940s, churches served both as dividing and unifying forces. Our Baptist Church saw itself set apart as the bastion of Christian truth and ethical propriety, with serious questions about the authenticity of other denominations, and especially Catholics. But when it came to support for the war, all Christian organizations closed ranks, seeing America and God working together for the good of the world and the Kingdom of God. This theme of Christian unity and support of the war will be seen later in Chapter 29 and the description of Memorial Day ceremonies.

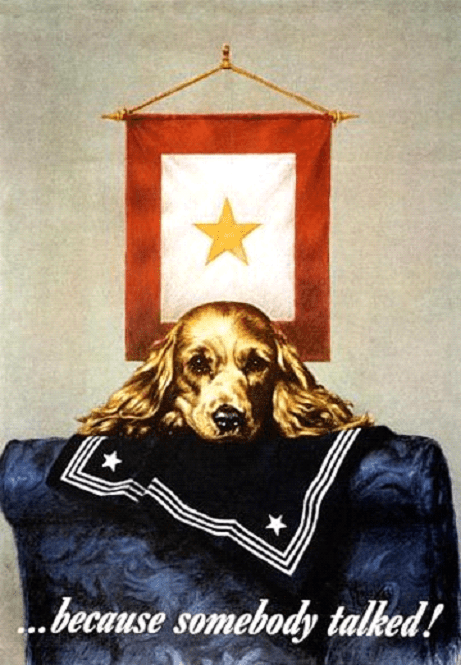

On the side wall of the church sanctuary hung an armed services flag, a grim reminder of the human cost of the war. Each blue star stood for a church member in the military. When we learned of a death in action, we honored the fallen hero in a special part of the Sunday church service, replacing his blue star with a gold star. In this way, our Baptist Church memorialized and sanctified the military death, seen as a sacrifice for country and religion.

In every church gathering, the preacher offered prayers for the protection of loved ones, including general petitions for all of our military personnel, and even naming individuals from our church in the armed forces. The preacher and the congregation assumed that “our boys” were risking, and even sacrificing, their lives for the good of the country and the work of God.

A March 19, 1943 article in the Democrat reports on the dedication service for a flag in this Baptist Church:

FORTY STARS IN

BAPTIST CHURCH

SERVICE FLAG

LEGION POST WILL CON-

DUCT DEDICATION SER-

VICES SUNDAY

A service flag bearing 39 blue stars and one gold star will be dedicated at the Baptist church Sunday morning. Havana Post No 138, The American Legion, will have charge of the dedication services.

Each star in the flag represents a boy in the service who attended church or Sunday school at the Baptist church .

[Excerpt from Chapter 23.]

In 1944 Dad shipped out, to somewhere in the Pacific, stationed on the battleship USS Missouri.

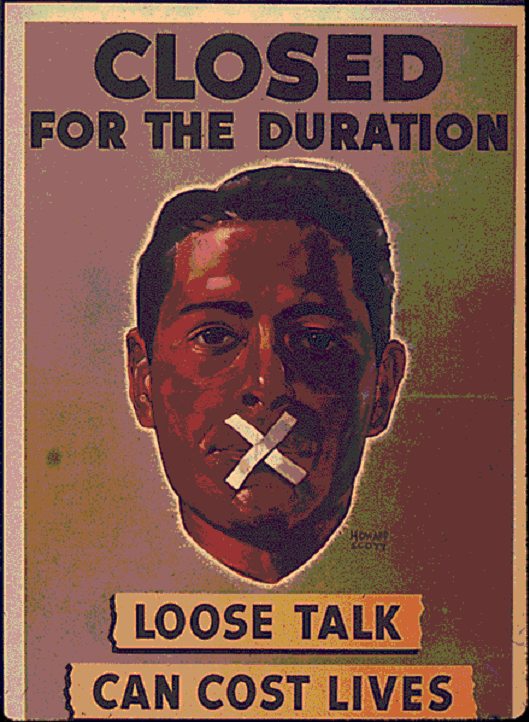

From that point our fears increased. It became difficult to get mail to and from the ship, and Daddy couldn’t write about where they were. It was bad enough when we were deprived of the presence of our father, but now that he served in a war zone, anything could happen.

Whenever I went to church, I hated to look at the armed services flag, and its field of many blue stars with a few gold stars. The ceremony for the death of a military man from our church, replacing a blue star with a gold star, was horrible to sit through. I experienced a mixture of many emotions. I felt very sorry for the poor family suffering the loss. At the same time, I was relieved that it was not our father.

Then came the realization that I had wished it was someone else’s loved one, and a sense of guilt overwhelmed me. The ceremony seemed to last forever, and even when it finally ended, I couldn’t get it out of my mind. My fear lingered— the next gold star could be for our father.

War always seems to inspire song writers. One song popular during the war was “Bell Bottom Trousers,” which can be heard on Youtube. Its opening lines are:

“Bell bottom trousers, and a coat of navy blue.

I love my sailor boy, and he loves me too.”

(Throughout the book, references to wartime songs enable the reader to listen to the same tunes that inspired patriotism during the early 1940s.)

If you liked these anecdotes, they’re all from At Grandma’s House, which you can now buy on Amazon.