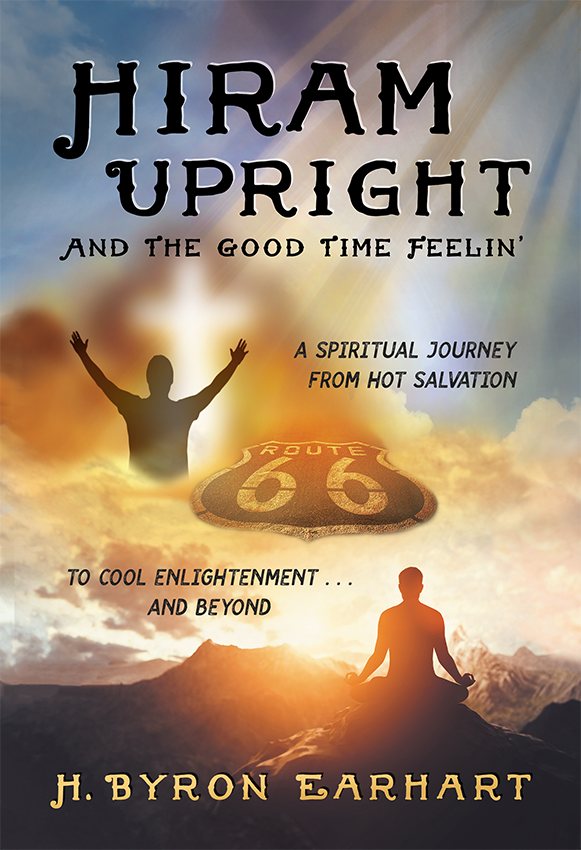

Meet the members of Hiram Upright’s clan, including a hyper-holy mom and an atheist dad, and the cast of characters he encounters during his cross-country trek: a sanctimonious minister, a devout girlfriend, learned and devious professors, a mysterious mystic, a Japanese war bride, a Japanese-American woman who is a meditation guide, a seductive troublemaker, and a famed Zen priest.

Join Hiram as he crosses the continent and explores meditation, Buddhism, yoga, and Zen before arriving at a spiritual destination that places him beyond these Asian traditions while he reconsiders his childhood faith.

As an author, my hope is that you enjoy tagging along on Hiram’s journey, and that this experience helps you appreciate more fully the journey that is your life. You can purchase Hiram Upright on Amazon.

Excerpt — Chapter One

Hiram Upright. That’s my name. As a kid I hated it, getting teased because it sounded so wacky.

As an adult, when I started my own spiritual movement, people accused me of creating this weird handle. “Hiram is so holy sounding, so Old Testament sanctimonious, and Upright is . . . well, so virtuous.”

But that’s the moniker my parents gave me at birth. Well, Mom came up with the name, and Dad just went along with it, like the other labels she picked for her kids.

My parents never showed any deep affection for each other. I don’t recall Dad ever saying, “I love you” to Mom, and he only bestowed kisses on her at her birthday parties, when my sisters got behind the two, forcing them into an awkward embrace and a brief peck. Their loveless marriage silently announced what they didn’t need to say out loud: “We had to get married, and we lived unhappily ever after.”

Mom and Dad were Sarah and George. The story of how they met is undramatically simple. He asked her out a couple of times in high school. In his senior year he invited her, a junior, to the prom. And they got married the summer after he graduated. Our family did not excel in mathematical skills, but even as kids we realized that the birth of Zack—short for Zachariah—in February the year after they got married, came less than nine months from the time of Mom and Dad’s wedding.

After Zack came Isaiah, nicknamed Ike. Blessed with two girls, Mom switched from the Old Testament to the New Testament, christening the first Mary, the next Martha.

By the time I came along, the fifth offspring, Mom left the biblical sphere and borrowed the first name of a revival preacher, Hiram Sweeney, who inspired her and, as she explained it, “restored my soul.”

If “Hiram” had gotten remodeled and supplied with a final “k” sound like my brothers’ names, I would have been called Hike. But no one knew how to shorten Hiram, so everyone used it in its unabbreviated, unadulterated form. In my teenage years, some buddies tried calling me “Hi.” For a few months, several kids greeted me, “Hi, Hi.” Fortunately, that novelty met a silent death.

We Upright kids just took it for granted that our household followed the Midwestern pattern for married life, family life. You went to high school, graduated if you were lucky, married someone you met in school, found a job and started raising kids, hoping to get by, living from paycheck to paycheck.

That’s how the world turned in central Illinois in the 1940s. We lived on the edge of Hanavan, a town of 4,500, renting a ramshackle farm house. It had a second story, but the first floor had been added onto so many times that the original structure remained hidden behind a jumble of lean-tos. The farm land had been sold off, orphaning the old homestead. In those days, long before the move-to-the-country fad, no one wanted such a marginal place. Farmers needed land that produced crops, not a house that ate up money with repairs. Working people wanted to be “in town,” where their kids could walk to school, and downtown provided grocery stores and retail shops.

Many of these old farm homes sat vacant, their roofs sagging like swayback horses, until a heavy snowstorm or high winds prodded them to reach their inevitable moment of implosion. Driving through the country, you could recognize the remains of one of these former homes by the pile of shingles and lumber and a crumbling chimney, all flanked by a rectangle of trees. In winter, a blanket of snow provided a temporary mantle over this debris; in summer the few flowers not completely choked out by the high grass, often rambling roses, thrust colored heads up to mark the grave of a previous habitation.

Our house had advanced well on its way to oblivion, on a permanent tilt, but still remained in the livable, pre-collapse state. The roof leaked, the steps slanted, the floors squeaked. The back porch, a lean-to, had started to lean away so much that daylight filtered in where the porch roof once met the house, revealing its progressive secession from its one-time union with the main structure. Brownish-gold tarpaper siding attempted to cover a plenitude of iniquities inflicted on the clapboard by amateur painters and inferior paint, but the sins of the past peeked through the tarpaper here and there, giving the exterior a multi-hued facade.

Inside, the decor suggested not so much decay as disrepair. Every faucet leaked. The foundation had shifted, causing the walls to crack and the building to settle accordingly. Doors had long given up their original intent of closing tightly, the door frames morphing from a rectangular to a trapezoidal outline. Only one room, our “parlor,” boasted wallpaper, which had started to peel away from the plaster, as if making an attempt to escape its dingy surroundings. For our parents as well as us kids, walls became a convenient site for nailing, screwing, taping, or thumb-tacking homework or a calendar, maybe a postcard or picture. We treated woodwork in a similar cavalier fashion. If a previous tenant had hammered a nail into a door jamb to hang a hat, we took the hint by pounding in our own personal nails.

The general state of dilapidation changed only when occasioned by absolute necessity, not cosmetic improvement. A holey screen didn’t need replacing in winter, only in warm weather, after a few nights when we all got eaten up by mosquitoes. A loose-fitting front or back door could wait until after the first frost.

Repairs in the house followed three rules. First, it had to be done by Dad, because our landlord wouldn’t provide any money or labor, and we couldn’t afford to hire anyone. Second, the fix had to be managed as cheaply as possible, preferably from the rag-tag materials and rusty tools in the shed, all left behind by previous renters. Third, any renovation was only temporary, just to patch up the place and make it livable for us, and when something gave way, as it always did, it got pieced together again. Dad tried his best, but more often than not his minimal handyman skills didn’t lead to improvement, they simply shifted the condition of disrepair to mis-repair.

The house had terminal architectural cancer, but our family remained oblivious to all these symptoms of impending doom, because we assumed we would escape before the house fell to pieces. Maybe the condition of the house did not concern us so much, because the state of our household mirrored the pathetic set of rooms we occupied. Like the dilapidated house, none of us even dreamed of turning our dysfunctional family relationships into a picture-perfect community. If we could somehow get along and muddle through, then individually and more or less collectively, we would survive and outlast the bonds that somehow brought us together.

Dad would certainly not be called a handsome man, yet his striking appearance made him an unforgettable character. People called his build wiry, or even bony, six feet tall and skinny, all muscle. He had a prominent ridge over his eyes, a beak for a nose, high cheek bones, sunken cheeks, and a pointed chin accentuating his angular face. Usually a cap with a long bill covered a shock of chestnut-colored hair. When he didn’t shave, his stubble revealed a reddish tint.

He seldom smiled. His infrequent and sudden laugh had a rough edge to it, as if covering up a scream of pain. If you’ve ever seen black and white photos of nineteenth century Irish coal miners surfacing after a long day underground, silent despair etched on their faces, you’d have a good image of my father.

Apart from his looks, what I remember most about Dad is that he worked. He worked hard. From early in the morning till late afternoon or early evening. He had breakfast and left the house before us kids got out of bed. When Mom wasn’t busy, she’d treat everyone to pancakes. The first ones up would eat the pancakes left over from Dad’s breakfast, and then we’d have to wait for Mom to fry some more. Mom had already packed Dad a lunch and a thermos of coffee.

When Dad was in high school, his own father died of lung cancer, probably the fringe benefit of stoking furnaces for twenty-five years at a local foundry that made plow shears. To help out his widowed mother, Dad worked after school and weekends doing lawn work, odd jobs, and especially trucking. A strong and willing worker, he gravitated to trucking and hauling. In Illinois in the 1930s and 1940s, coal provided the main heating fuel. Dad got most of his jobs and best pay delivering and unloading coal to local homes. At first he worked as a helper, but was so dependable and honest that eventually the boss trusted him to drive a truck to the nearby coal mines by himself and make deliveries. When he graduated from high school, he went from part time to full time without ever applying for a job or being hired.

The England Coal and Stone Company employed Dad. As a kid, I said, like the rest of the family, “Dad works for England.” I didn’t know what that meant, and actually believed it had something to do with the country of England. I liked the idea that my father worked for a foreign country. When I began helping my older brothers deliver newspapers, and they told me, “That’s old man England’s place, the guy Dad works for,” I felt disappointed. Dad just worked for a local man.

Then I looked over the England house, and my spirits perked up. An impressive three-story structure, it had round columns supporting a porch that half-circled the front and south side. The clapboard on the first and second story was painted a slate blue, offset by weathered brownish wood shakes on the roof and the exterior of the third story. Several large picture windows on the first floor were balanced by rectangular windows on the second floor and round windows on the third. So now I could say, “Dad works for England, the owner of the big blue house at the top of Plum Street hill.” Compared to our rickety collection of lean-tos and add-ons, Mr. England’s edifice ranked as a mansion, of unique design and singular construction.

Of course, neither Dad nor our family had much direct contact with Mr. England. When I first heard the story, “A Christmas Carol,” and on every retelling, I pictured Scrooge as Mr. England. Not because England was mean, but because every Christmas he gave us a turkey. Everyone who worked for England Coal and Stone got a turkey, even the old maid bookkeeper.

Dad deserved that once-a-year turkey, because he always put in a good day’s work. When he had a load of coal to pick up, he arrived at England’s office by 5 or 6 A.M. to get the truck, then made the thirty-minute trip to the coal mine, and waited his turn to have the truck weighed empty. Then he moved the truck under the overhead conveyor and got loaded with coal, weighed again, drove back to town and unloaded.

He backed up to a house, hooked a metal chute to the bed of the truck, slanting it through an open basement window into the coal bin. He shoveled coal down the chute until it was full, then went down in the basement to clear the coal away, in one motion scooping and slinging it into the far corner.

All this shifting of the coal kicked up a pitch-black cloud of dust. As this ebony snowstorm floated above the coal chute into the bright sunlight, the black specks turned into tiny diamond sparkles. With the bed relieved of its black cargo, he pulled the truck onto the street and cleaned up stray pieces that flecked the lawn. Then he hurried to the mine for another round trip.

Some days, especially in late summer or early fall, he’d make four, or even five forays to the mine. In spring and summer he hauled gravel for driveways, and fill dirt for buildings and gardens. We could tell what Dad had trucked that day by the color of his clothes and skin: black for coal, brownish red for dirt, and dusty white for gravel.

Excerpt — Chapter Four

One Saturday morning Mom sat at the kitchen table in her gown and robe, her weekend vigil for her wayward husband. Or so we thought. Mom’s face looked more serious and tired than I had ever seen. Mom insisted on making us a big breakfast of pancakes and waited until we ate our fill, saying she wasn’t hungry.

“Children, I have to talk to you. Your Dad has gone and he’s not comin’ back.”

When each of us tried to ask questions, she held up her hand to silence us.

“Let me try to tell you this as well as I can. Your father’s left town. He’s gone away and there’s nothing we can do to get him back. Now we have to do everything we can to hold this family together. We’ve got to . . . .” she faltered.

Mary and Martha went to Mom and held her in a dual bear hug. “Mom, we’ll help you,” they both said.

Zack had been silent, almost sullen as he wolfed down his pancakes. Now he stood up, not moving toward Mom, but speaking for everyone. “I’ll help. We’ll all help . . . won’t we, guys?”

Ike and I nodded in agreement, not knowing what we had assented to.

Mom said slowly, “The first thing I’ve got to do today . . . is talk to Mr. Jefferson. I’d like to keep this house. It’s been good to us.”

Mary and Martha were still comforting Mom as we three guys shuffled out of the kitchen.

I felt like a passenger on the Titanic, sensing the tilt of the ship, but still not realizing the seriousness of the looming disaster. I asked Zack, “Why wouldn’t we do what Mom said, stick together?”

Zack shouted, “You little dumb shit. Don’t you see that without Dad, with no money, we’re liable to be split up and sent to foster homes or orphanages?”

His words struck me like lightning bolts.

Mom needed to buy groceries, but she had a problem. Usually, we got them at the nearby grocery, C and D, ran a tab, and at the first of the month paid it off. Dad had skipped out the last of the month, and we couldn’t charge any more on credit at C and D until we paid our bill. She’d have to walk four more blocks to Anderson’s Grocery, so Martha said she’d go along and help carry things. Martha and Mary had already talked. As soon as Martha was out of the house with Mom, Mary announced, “We all need to go to church with Mom in the morning.

Zack objected, “Hell, Mary, us guys need to get working on that fencerow. We can’t really take on much other work until that’s done.”

“Zack, we appreciate what you’re doing, but this is important to Mom. Church is everything to her, and she’s got to be able to walk into that church with her head high, showing the support of the family. Probably everyone in town knows what’s going on.”

“Mary, you know it’s that Painter woman, don’t you?”

“No! I was afraid of something like that. Still, I had no idea . . . .”

“Yeah, so he’s not coming back.”

Mary frowned. “That’s all the more reason for us to go to church with Mom. If you know about it–where did you find out?”

“At the pool hall.”

“The Hanavan Newspaper, huh? Well, you can be sure the word is all over town.”

When Martha and Mom came back with groceries, Zack told Martha about Dad’s lover. Martha shook her head. “Hah! And he tells Mary and me, ‘Don’t get into trouble.’”

Mary put her hands over her ears. “Martha! I don’t want to hear about it.”

Zack said, “Okay, Mary, we’ll go to church tomorrow. But the deal is only for tomorrow. Right, guys?”

Ike and I nodded. “Right.”

Walking into church that Sunday felt like climbing the steps of a gallows for a hanging. Meeting the church members, who all must have known Dad deserted us, amounted to collective humiliation. When we arrived at First Baptist, I felt that the whole congregation had turned out to witness us shuffle in. People spoke so solicitously. “Good morning, Sarah. Why you’ve brought your whole family. How are you today?” They knew perfectly well she was dying with shame.

The shaking of the earth I had felt on Saturday followed me into church. I daydreamed through Sunday school, and then we reassembled to sit with Mom in church, the six of us lined up in a pew on one side of the sanctuary. Now the trembling crept up my legs and settled in the pit of my stomach, tying it in knots. My heart raced and my head felt woozy. When we entered the sanctuary, I got sandwiched between Mary and Mom, with Martha on the other side of Mom. Mary and Mom had their heads bowed in prayer, moving their lips. Martha looked down, hands in her lap. I thought I might faint and embarrass everyone. Seeing Mary and Mom praying, I thought to myself, “God, help me. Help me to be strong. Not pass out.”

The five minutes or so of hubbub between Sunday school and church had seemed an eternity. Praying seemed to help calm me. Then I felt a chill of fear as I realized more fully the danger ahead: “f-f-foster home or or-or-orphanage.” I prayed even more earnestly. God help us!

Our whole family needed help. I couldn’t quite grasp how God could help us. God couldn’t cut trees and brush out of the fencerow or hand over the $50 rent money or provide groceries. Maybe all he could do was help us make it through that church service. At least God could help us help Mom.

The service started with hymns and a prayer, and we had to stand. I was happy to find that, putting my hands on the pew in front of me, my rubbery legs could support me. I held a hymnal with Mary and mouthed words to a tune I didn’t know. When I sat down, the trembling began to move up my body again and I prayed to God to help me stop shaking. Mary gave me a dirty look as if telling me to sit still. I looked away from her and gazed above Reverend Poole, our minister, who was giving a never-ending introduction to a revival preacher. I saw behind the minister the bigger than life painting of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, with flowing dark brown hair and compassionate face, hands outstretched. I had seen this painting lots of times, whenever the Sunday school sang a hymn for the church. I always thought Jesus was looking far away, focusing at the back of the church. But today his eyes seemed fixed on me, staring right at me.

By now the revival preacher, Reverend Witherspoon, had whipped up the congregation. He chastised them for their sins, warned of everlasting punishment, and held out the promise of never-ending paradise, reunion with the God from whom they had alienated themselves. “Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, the answer is with us. It has never left us. It is right here. Right behind me.”

He turned dramatically to extend his palm almost to the painted hands of Jesus. “Christ welcomes you now. The same as he welcomed you yesterday. He will do so again tomorrow, but why wait? Who knows what tomorrow brings. A well-known prayer states: ‘If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take.’ Why not let the Lord take possession of your soul now? He can heal your wounds, solve your problems, remove your worries.”

The church members warmed to the message with, “Amen, brother,” and “Praise the Lord.”

“Brothers and sisters, let’s all stand up and sing that great testimonial, ‘Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus!’”

I followed Mary and Mom in getting to my feet, and could sing this song by heart. But my focus stayed on Jesus, as his gaze seemed to be on me. We remained standing after the hymn, and the preacher urged everyone to “Give God the glory.”

What he said after that I lost track of. Mother and Mary, and then Martha, raised their hands with fingers spread apart and shook them. My arms were leaden anchors unable to move. Then Jesus’ outstretched fingers extended their power to mine and lifted them up, filling my hands with a pulsating energy. I was one with Jesus and he was one with me. The movement in my hands filled my body with a rhythmic harmony I had never known before. Lost in reverie, I got jolted back to reality as Mary nudged me. Everyone else was seated.

The remainder of the service turned into a blank. I was in personal communion with Jesus. After the benediction, I walked, or floated, out of the church. Mary and Martha hovered around Mom as she received the greetings of “How are you doing, Sarah?” and “If we can help you out, let us know.”

I walked over to Zack and Ike. “Did you feel that?”

“Feel what, Hiram?”

“In church . . . .”

“Did you get the good time feelin’, Hiram?” Zack quipped.

“Yeah, I . . . guess.”